Hey, Hannatu here 👋

Africa’s next big protein source doesn’t moo, cluck, or swim; it crawls.

Across the continent, cities generate 125 million tons of organic waste annually.

Food scraps, spoiled vegetables, brewery grains, the stuff everyone calls garbage.

But innovative entrepreneurs see something else: protein.

They’re feeding this waste to insects, and those insects become high-protein animal feed.

It’s a simple loop that cuts farmer costs at the source.

If you want to understand why that’s important, let me tell you about…

The Feed Trap

In Kenya, for example, raising chickens is a brutal business model.

About 65% of all the production costs go to just one thing: feed.

To raise a single flock of 50 birds from chick to market, a farmer spends about Ksh 27,300 ($211).

And today, that protein comes from soybeans or fishmeal, usually imported from thousands of miles away.

This is the Feed Trap.

Farmers are bleeding money to import 4 million tons of soybean oilcake.

Meanwhile, African cities are drowning in 125 million tons of organic waste annually.

Soybean Oilcake. Image Source: Novoaltaysk Oil Extraction Plant

There’s a scarcity problem (feed) and a surplus problem (waste).

But what if one could solve the other?

The Six-Legged Bioreactor

The solution isn't a new crop. It's a bug.

Specifically, the larvae of the Black Soldier Fly (BSF).

The Black Soldier fly larvae. Image Source: Manna Insect

Most people see a pest. Innovative entrepreneurs see a biological machine.

These larvae are nature's supreme decomposers. They are tiny bioreactors that turn trash into treasure.

They process twice their own weight in waste every day.

One ton of larvae can consume four tons of waste in just two weeks.

And they require almost no land and minimal water.

Some entrepreneurs have compared this to the status quo and are finding a better solution.

To get protein from fish, for example, you need 10kg of feed and 15,000 liters of water.

To get it from soy, you need acres of arable land and fertilizer.

To get it from insects? You just need a warehouse and the trash the city throws away.

A space the size of a basketball court can produce tons of insect protein monthly.

And the environmental benefits compound.

Insects don’t need irrigation or deforestation.

They cut methane from landfills.

And they feed on what cities throw away.

For farmers, a 15–20% drop in feed costs can mean survival.

For Africa, it means keeping billions in local economies instead of sending them overseas for soy and fishmeal.

And This Startup Figured It Out

One of the agtechs turning this massive potential into reality is in a Tanzanian Agritech startup, Biobuu.

The company, founded by Kigen Compton and Matthew Haden in 2017, didn’t just rush onto the scene.

It spent three years studying the larvae of the Black Soldier Fly, then registered operations with one mission: to turn East Africa’s organic waste streams into affordable, local protein.

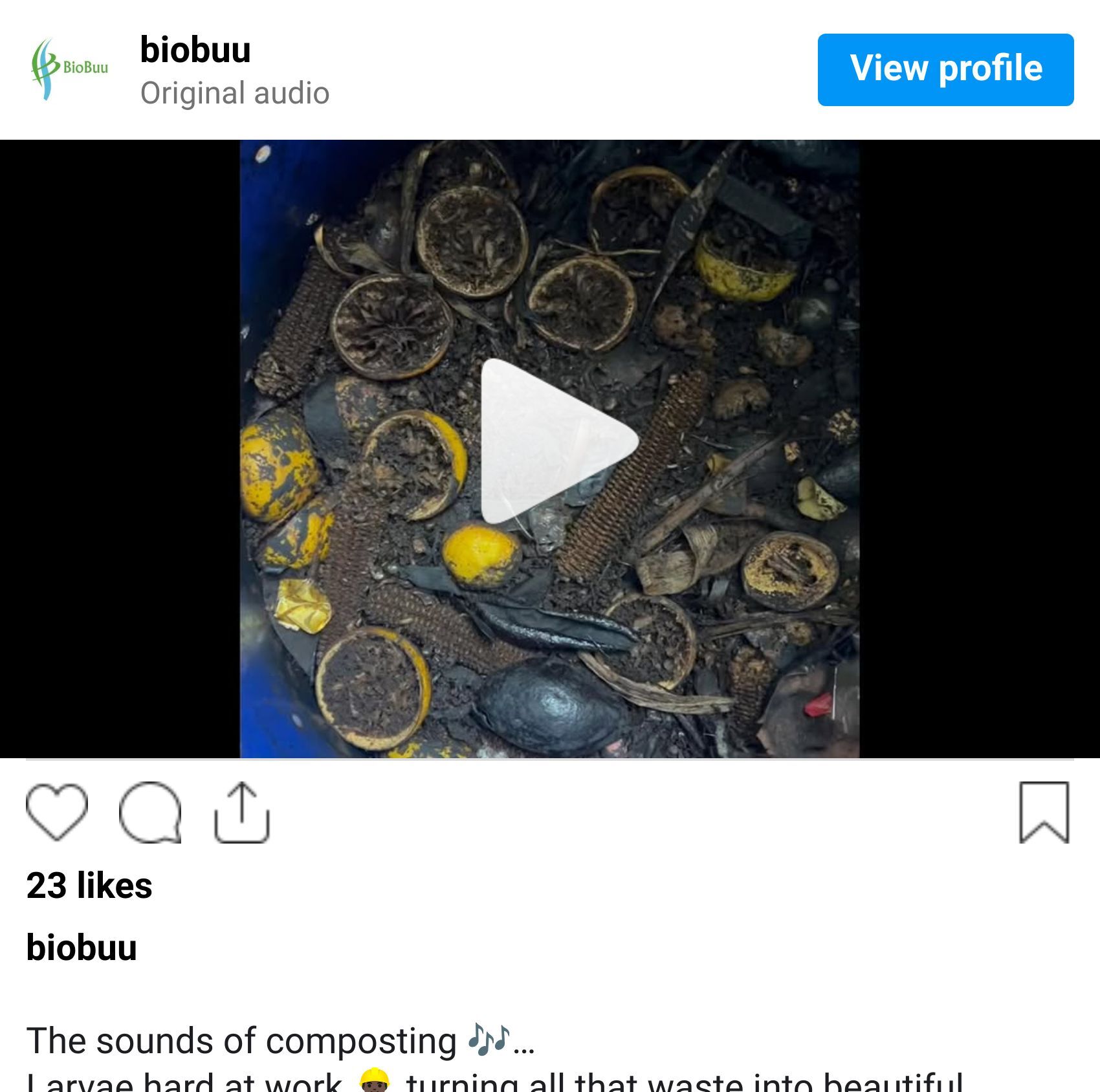

Featured by the BBC, Biobuu is now more than just a science experiment; it is a waste management utility.

Every single day, their "maggot workforce" consumes 20 tons of organic waste.

The Black Soldier Fly Larvae at Biobuu. Image Source: Biobuu.

To date, they have diverted 45,000 tons of waste from landfills.

By doing so, they’ve cut methane emissions by 67% compared to traditional disposal methods.

Their raw material isn’t imported soy. It’s market leftovers, food processing by‑products, and household and restaurant scraps.

Waste that would otherwise rot in dumps around Dar es Salaam and coastal towns is instead trucked to Biobuu’s facilities, where it becomes soup for the maggots to eat.

The larvae then spend 1–2 weeks feasting on this combined waste, growing up to 10,000 times their size in the process.

At the end of this frenzy, Biobuu harvests them. This is where the waste transforms into a trifecta of products:

1. The Poultry Feed (Kuku Bonge) They dry the larvae into Kuku Bonge. It’s a "no fluff, no filler" feed containing 48.9% protein and 26% fat. Because it mimics a chicken's natural diet, it offers better feed conversion than soy, allowing farmers to grow birds faster for less money.

2. The Soil Healer (Biobuu Organic Fertilizer) What the insects don't eat is just as valuable. The larvae leave behind a nutrient-rich manure (frass). This organic fertilizer is currently regenerating soil on 350 farms, boosting maize and tomato yields without the chemical burnout of synthetic fertilizers.

3. The Curveball (Kibo Dog Food) Biobuu also proved that insect protein isn't just for farm animals. They launched Kibo, a vet-approved, insect-powered dog food. Because it skips the carbon-heavy beef and lamb supply chain, Kibo has a negative carbon footprint.

It is likely the only dog food in East Africa that helps the planet with every bowl.

The impact of this model is tangible.

Biobuu has created 120 local jobs, proving that waste can drive employment.

Kibo Dog Food. Image Source: Biobuu

But beyond turning insect larvae into feed, another startup in Uganda, Proteen, turns it into another valuable product: fertiliser.

The company feeds organic matter to the BSF larvae. After 10 days, the larvae are terminated in their own manure.

They become a part of the fertiliser.

This fertiliser is then used for farming activities.

So larvae can be fertiliser and feed.

Crawling Towards Scale

But can this feed model really compete with the global soy giants? Biobuu thinks so.

In January 2025, the company commissioned a new, state-of-the-art feed mill in Tanzania.

Biobuu’s 5,000 ton/hour feed mill in Tanzania. Image Source: Biobuu

This moves them from "startup" to "industrial player," capable of churning out massive quantities of feed to meet the demand from local farmers.

However, for the rest of the continent, the insect protein revolution is still crawling toward scale.

The first challenge is surprisingly unsexy: the recipe.

Animal feed isn’t just “ground stuff in a bag.” It’s more like a carefully balanced smoothie.

Farmers need the right mix of:

Energy (fats and carbohydrates).

Protein.

And amino acids, the tiny building blocks inside protein that drive growth and immunity.

That mix is what nutritionists call the nutritional profile.

For decades, most feed recipes in Africa have been built around soy and fishmeal.

Their profiles are well understood.

And swapping in a new protein like insects doesn’t mean you can just replace “1 kg of soy” with “1 kg of larvae” and hope for the same results.

It doesn’t work that way.

Feed mills have to reformulate the entire recipe, and tweak the amino acid levels, energy content, and vitamins so chickens and fish still grow fast, stay healthy, and don’t get sick.

That takes testing, time, and trust.

Regulation is the next hurdle.

In most African countries, feed laws were written for conventional ingredients like soy and fishmeal, not larvae.

Without clear rules saying “this is allowed, under these conditions,” startups operate in a grey zone.

The European Union (EU) banned insect protein after the BSE outbreak in the 1990s and only approved it again in 2021, starting with aquaculture.

Africa doesn’t need to wait decades to move.

Rwanda and South Africa are ahead, but elsewhere, entrepreneurs are still lobbying for recognition.

Then there’s perception. Some farmers hesitate to adopt insect‑based feed because it feels unfamiliar.

Advocates use a simple reminder: chickens naturally eat insects. This is just helping them do it better.

Capital and logistics are another bottleneck.

Contaminated waste can kill entire larval colonies. Plastics, chemicals, or spoiled meat destroy batches.

Farmers must carefully source and sort waste.

In most cities, collection systems barely exist. Farmers negotiate with markets and restaurants individually.

Success in insect farming demands reliable collection systems, partnerships with cities and factories, and serious operational discipline.

But investors are starting to notice.

MagoFarms is seeking $1.5 million to build a large-scale facility.

All of them want to prove they can make the unit economics and supply chains work at scale.

The View Ahead

Fish farms might crack the code first.

Aquaculture already struggles with soy’s anti-nutritional factors. They’ve developed workarounds for years.

Insect protein actually simplifies their formulations. That’s why investors watch aquaculture closely.

If insect protein captured just 10% of Africa’s feed market, it could:

Redirect $600 million in spending from imports to local producers,

Create thousands of jobs, and

Divert millions of tons of waste from landfills.

For the continent’s farmers, that means lower feed costs and a stable supply.

For cities, cleaner waste management.

For the planet, lower emissions.

Africa’s protein revolution isn’t on four legs or fins, it’s on six.

Would you feed your chickens, or yourself, with insect protein?

Cheers,