Hey, Isaac Onyeakagbu here 👋

In Ibadan, south-western Nigeria, something quiet and radical is growing behind houses, churches, and campus walls.

Young graduates are filling ordinary plastic bags with sawdust and grain.

A few weeks later, those bags burst into clusters of white oyster mushrooms, enough to feed families and fund small businesses.

Each bag costs about ₦200 ($0.14) to make. Each harvest sells for around ₦2,000 ($1.38) or more.

A 10x return, grown from what used to end up in landfills.

If you zoom out, the opportunity gets even bigger.

In Nigeria, there are over 1,300 sawmills generating 1.8 million tonnes of sawdust every year.

In Oyo state, 135 sawmills pump out waste daily.

And plastic? Nigeria discards 2.5 million tonnes of plastic bags annually.

Walk past any furniture workshop in Ibadan, the capital city of Oyo, and you'll see it.

Sawdust piles higher than a person. Plastic bags are discarded and forgotten.

But a growing group of young people in Ibadan have started seeing these piles differently.

Where others see rubbish, they see raw materials.

What seems like the city’s biggest environmental headache looks, to them, like an untapped food supply.

So in backyards across the capital, something surprising is happening: plastic bags once headed for the dump are being filled with sawdust, steamed, seeded with mushroom spores, and transformed into food.

Dinner is sprouting from what the city throws away.

Feeding a City, Fueling Dreams

In Nigeria, food prices climb faster than most people's incomes.

Food inflation hit 39.9% in November 2024.

The numbers on every plate tell a brutal story:

Eggs: Up by 136%. A dozen that cost about ₦1,200 ($1.20) in 2023 now averages ₦2,834 ($1.95)

Beans: Half a kilogram now costs ₦2,720 ($1.88), nearly triple the 2023 price.

Onions: The biggest shocker. A single kilo jumped to ₦2,058 in December 2024 ($1.42).

And it's not slowing down.

Meanwhile, the labor market is squeezing the next generation. About 6.5% of Nigerian youth are officially unemployed.

The picture is even grimmer for those with a secondary education, where the unemployment rate spikes to 8.5%.

Oyo State does better than most. With a 2.0% unemployment rate, it's one of the lowest in Southern Nigeria.

But statistics don't feed families.

Even the employed struggle when food prices triple overnight.

Mountains of sawdust in Oyo, Ibadan. Image Source: Renewable Energy World

So you have hungry youth without jobs, and mountains of waste nobody wants.

But what if these problems could solve each other?

The ₦200 Tech Stack

A handful of graduates in Ibadan decided to answer the question.

They grabbed some plastic bags, collected sawdust from local workshops, and started experimenting.

They didn't have the capital for greenhouses. They didn't have land for rows of crops.

But they realized they didn't need them.

They found that if you treat the waste just right, it stops being trash and starts being a bioreactor.

The answer began growing in backyard corners across Ibadan.

Here’s the secret: mushrooms don’t need soil.

They thrive on decaying organic matter, like sawdust.

Farmers mix sawdust with water and a little grain, pack it into plastic bags, and steam the bags to kill bacteria.

Then they add mushroom spores (called spawn) and store the bags in dark, humid corners.

In 2–3 weeks, white mycelium spreads through the bag.

A few days later, mushrooms push out, soft, white, and ready for harvest.

Oyster mushrooms sprouting from recycled organic substrate bags. Image Source: Isaac Onyeakagbu

Each ₦200 ($0.14) bag can produce up to 700 grams of mushrooms in a month.

Multiply that by dozens or hundreds of bags, and a micro-farm is born.

It’s low-tech. It’s sustainable. And it turns waste into food.

And it’s a perfect circular economy model.

For most growers, this isn’t just about profit. It’s about control and resilience.

Oyster mushrooms sell in Ibadan markets for ₦2,000 ($1.38) to ₦3,000 ($2.07) per kilogram, while each grow bag costs less than ₦200 ($0.14).

One study concluded that small farmers can earn nearly twice their investment.

In a city where jobs are scarce and food prices are volatile, mushroom farms offer a reliable income and food supply.

And the spores spread fast

Once the "code" was cracked, the ecosystem clicked into place.

It wasn't just scattered experiments anymore. Institutions stepped in to scale it.

Government research labs like FRIN ran community demos that showed how sawdust could become food.

NIHORT, Nigeria's horticulture research hub, joined in. They added mushroom production to their training programs for unemployed youth.

Universities like UniJos and Babcock University turned it into hands-on programs.

The MushWealth project started training thousands. Babcock's mushroom farm won awards and got coverage in the Independent Newspaper.

What began as scattered experiments became an ecosystem.

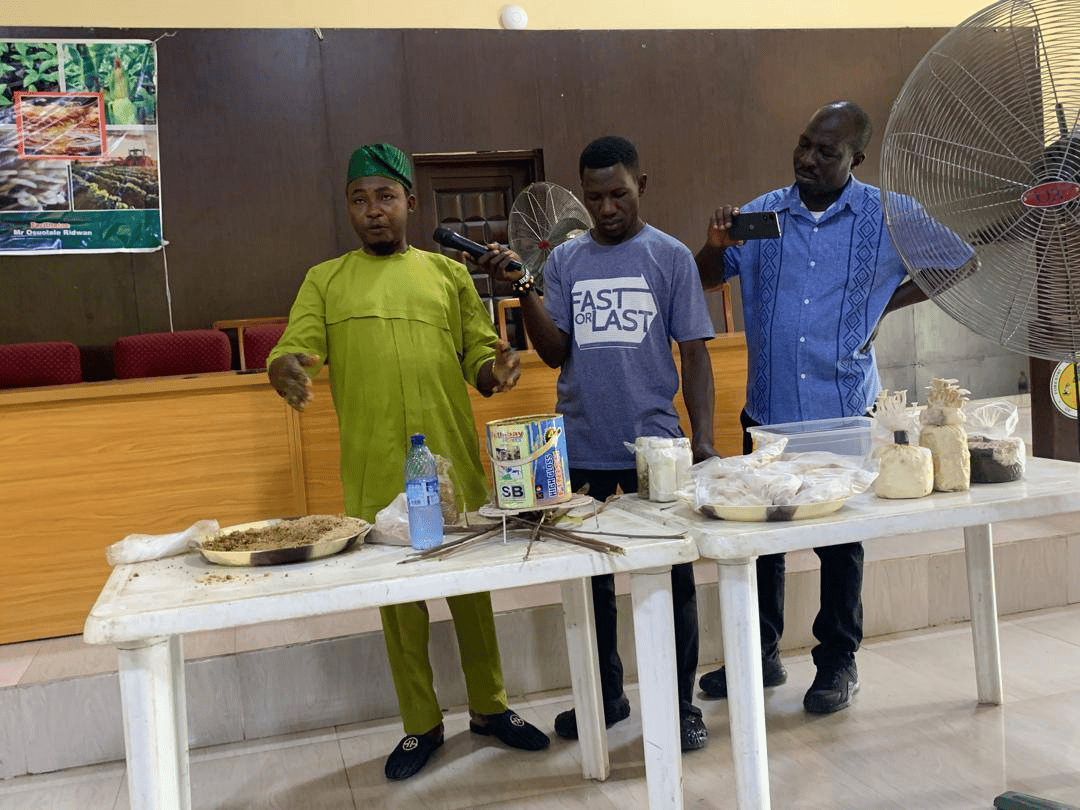

A mushroom production workshop at FRIN's Ibadan campus. Image Source: FRIN Official

Across state neighbourhoods like Mokola, Oje, Jericho and Agbowo, small mushroom farms now sprout behind homes, schools, and churches.

Research labs proved the science worked. Universities gave it structure. NGOs connected farmers to buyers. Private projects brought scale.

The MushWealth project alone is training 2,000 young people, with 1,600 expected to start their own mushroom businesses.

Across Ibadan and even Nigeria, young people are mixing sawdust with mushroom spawn, growing food where others see trash.

"I've learned I can improve my financial status by converting waste into wealth," says Priscilla Ibrahim, who trained in Niger State through one of these programs.

Her trainer, Hajiya Hadizat Isah, is pushing farmers to see potential everywhere: rice husks, straw, sawdust.

That principle is now standard practice in Ibadan.

"Mushroom farming is the key to efficient transformation of waste to wealth in Africa," a University of Ibadan study concluded after testing how well mushrooms grow on sawdust and rice straw.

Even experts are paying attention.

Prof. Sami Ayodele, a mushroom plant scientist at the National Open University of Nigeria, believes Nigeria could earn ₦1 trillion ($691 million) annually and create 30 million jobs if the mushroom sector scales properly.

In practice, it started humbly: a workshop in a community hall, a student taking a sample home, a carpenter swapping sawdust for grow bags.

But what began as experiments is now seeding real businesses.

Classrooms turned into farms. Sawmills became supply chains. And Ibadan's mushroom economy took root, one bag at a time.

"We didn't think mushrooms could be this profitable," says a student at FUTA who took a mushroom cultivation course. "Now we see how waste can become business."

They’re run by young people, many without prior farming experience, who learned to mix sawdust, grain, and a little science.

Some now train others. Some sell to markets and local eateries. Some simply grow to feed their families.

The model is simple: collect waste, add science, grow food.

The first seeds of change

Mushroom farming solves multiple problems at once.

It cleans up sawdust that clogs drainage systems. It reuses plastic bags headed for landfills. And it creates income without needing acres of land.

Waste that once clogged drains now feeds families.

And it’s changing how young people see agriculture.

“We used to think farming was for old men in the village," notes a graduate from Ibadan. "Now, farming looks like science, and it fits in your kitchen.”

Can this small movement feed more than just a few families?

Experts believe it can.

According to FAO reports, edible mushrooms are rich in protein, low in fat, and grow in nearly any climate.

With better funding and access to training, Nigeria’s urban mushroom production could scale tenfold in the next decade.

At the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), just a few miles from Ibadan's city centre, researchers are testing new mushroom strains that grow faster, need less water, and can handle heat.

Even startups are locking in too, finding ways to turn waste into treasure.

In Tanzania, BioBuu is collecting organic waste and converting it into animal feed and fertiliser using insect-based bioconversion.

In Ethiopia and Kenya, Kubik turns plastic waste into interlocking building bricks. These bricks are cheaper than concrete, carbon-negative, and allow for rapid construction of schools and homes.

If this scales, Ibadan won't just solve its waste problem. It'll show other African cities how to feed themselves from what they throw away.

Today, hundreds of young people across Ibadan are turning waste into food.

Each plastic bag is a small business. Each harvest proves it works.

Tomorrow, this could be how every African city feeds itself.

One bag of sawdust at a time.

Do you believe micro-farms like these could feed an entire city?

👉🏾Tell us here.

Cheers,

Isaac Onyeakabgu is a food science and technology student with a passion for solving problems, whether in the lab, the boardroom, or the digital world.

What did you think of this week's edition of Ag Safari?

Join Ag Safari

Ag Safari is the go-to newsletter for anyone curious about agricultural innovation and potential across Africa. Every week, we deliver tactical insights, news, and founder-led advice straight to your inbox.