Hey, Hannatu here 👋

Did you know that you can tell someone's salary by their fruit bowl?

Or if they have one at all.

In Lagos, eating an avocado marks you as middle-class.

In Jos, mangoes from your compound tree signal you're broke.

And in Abuja, eating blueberries with your pancakes screams you come from money.

Across Nigeria, produce has become a class marker. It's as telling as the type of car you drive.

Look at any fruit hamper or gift basket. The contents are a status barometer.

Berries and kiwis mean wealthy people.

And it doesn't matter if the strawberries are from Jos or the Netherlands; if they're in the basket, money was spent.

Apples, plums and grapes signal middle-class.

Garden eggs, magarya, palm fruits? They don't even make it to the baskets. They’re too common for a gift meant to signal status.

This isn't about where fruits come from. It's about what they cost.

The Hierarchy Is Real

Elite fruits cost elite money.

Berries, kiwis, peaches: these scream disposable income.

In Nigeria, one punnet (125g) of blueberries costs ₦5,500 ($4).

Grapes cost ₦6,500 ($4.6) for a 500g bunch.

A kilogram of imported passion fruit costs ₦35,000 ($25).

Even strawberries are expensive; Nigerian-grown ones cost about ₦3,500 ($2.5) per kilogram in Jos markets in harvest season.

Strawberry farming in Jos, Nigeria. Image Source: Daily Trust

In large supermarkets, imported strawberries sit in plastic containers and cost about ₦20,000 ($14) per kilogram for a fruit that rots in three days.

Middle-class folks reach for apples.

While no apples are native to Nigeria, farmers in places like Kaduna still grow them.

But at ₦800 ($.5) per fruit, they're still not cheap.

"An apple a day…" is definitely not for lower-class Nigerians. That'd cost ₦24,000 ($17) monthly for one person, in an economy where the average person earns between ₦50,000 ($35) and ₦70,000 ($50).

Some doctor visits come cheaper.

Everyone eats bananas, pineapples, oranges, and watermelons.

They're the democratic fruits. No status, just sustenance.

You'll find them everywhere. From large crowded markets to fancy supermarkets.

You can even find some in slices hawked on trays around your nearest junction. They’re the vitamins for the people.

Then there are the bottom-tier fruits: fruits that flourish in the local climate and quite literally grow over your head.

Garden eggs, African star apples (agbalumos), cashews, guavas, soursop, magarya (jujube fruit), grapefruits from your neighbour's tree, and mangoes (when they’re in season).

African star apples (agbalumos), garden eggs, and margaryas (jujube fruit)

They're nutritious, sometimes even more so than the expensive ones.

While members of the middle class may occasionally buy them to satisfy a nostalgic craving, they are frequently seen as mere local staples rather than desirable fruits.

This class divide didn’t appear out of nowhere.

To understand its origins, let’s dive into a bowl of the…

The Colonial Fruit Salad

Before colonialism, West Africans ate what grew here.

Baobab. Tamarind. African star apple. Bush mangoes. Desert dates.

Markets sold magarya, black plums, and African breadfruit. These fruits fed kingdoms for centuries.

Tamarind and African Breadfruit.

Then Europeans arrived with their own fruits.

British colonials in Lagos wanted apples from England and grapes from France.

The Portuguese brought citrus varieties.

But they didn't just import fruits; they imported hierarchies.

These colonial administrators established import chains specifically for European produce.

Ships brought apples to Lagos ports.

Railways moved them inland.

And cold storage facilities were built, but only for foreign fruits.

But local fruits? They stayed in the "native markets”.

Schools run by missionaries served imported fruits. Government houses stocked European produce.

The message was clear: advancement meant eating what Europeans ate.

Post-independence, nothing changed. The infrastructure remained. The psychology stuck harder.

New African elites inherited colonial tastes along with colonial offices. Success still meant eating like Europeans.

Our taste buds literally changed.

Researchers call it the "colonization of taste".

And generations grew up associating sweetness with imported apples, not local agbalumo. Status with grapes, not garden eggs.

Today, Nigerian farmers grow some strawberries in Jos and Katsina, and grapes in Kaduna.

But supermarkets still prefer imported versions.

The "Product of Netherlands" label adds prestige that "Made in Jos" can't match. Same fruit, same nutrition, different passport.

Sixty years after independence, we're still eating colonial hierarchies.

Aspirational Eating and The Algorithm

Social media turned up the volume. We eat what we think successful people eat.

Now, avocado toast isn't just food. It's a lifestyle statement.

It doesn't matter if the avocados are from Kenya or Mexico; at about ₦7,000 ($4.8) per kg, the price tag is part of the performance.

Food bloggers show us smoothie bowls with berries, and parfait vendors top their yoghurts with almond nuts. That's how to eat "clean."

They rave about antioxidants in blueberries. Vitamin C in kiwis. Fiber in expensive apples.

Young Nigerians screenshot these posts. They make grocery lists of "superfoods" that cost super money.

What the wellness influencers rarely mention is:

Guavas have four times more vitamin C than oranges; 100g gives you 380% of your daily needs

African star apple (agbalumo) is packed with vitamin C and calcium.

Cashews also have five times more vitamin C than oranges, plus iron!

Soursop provides vitamin C, fiber, and potassium

Magarya offers vitamin C and antioxidants.

Garden eggs support heart health and blood pressure.

So young people buy ₦5,500 ($3.8) blueberries for antioxidants. Meanwhile, local guavas have more vitamin C.

They buy expensive apples for fiber. Meanwhile, mangoes have fiber plus vitamins A and C, folate, potassium, and copper.

We're paying premium prices for nutrients we already have. The health benefits grow on trees here. Literally.

The Infrastructure of Eating Rich

There’s another hidden tax in this fruit hierarchy: infrastructure.

Elite fruits aren't just costly, they're high maintenance too.

Berries need refrigeration within hours. And grapes demand consistent cold storage, whether imported or locally grown.

You need reliable electricity, a working fridge. Low-income households can't play this game.

Traditional fruits understand reality.

Mangoes sit on the counter for days.

Garden eggs last a week without refrigeration.

Soursop, cashews, grapefruits, they don't need pampering. They evolved here. They know the power goes out.

Food researchers have long noted that African indigenous vegetables and fruits (AIVs) have better heat tolerance and post-harvest shelf life.

Your fruit bowl doesn't just reveal your income. It exposes your electricity situation, too.

The Low-Hanging Truth

Young Nigerians are growing up believing good nutrition has a price tag.

That health comes from expensive fruits only.

We've convinced ourselves wellness requires certain fruits, the ones that cost more, whether imported or locally grown at premium farms.

The real tragedy?

Nigerian farmers who grow "premium" fruits can't access the same markets as importers.

Strawberry farmers in Jos watch their produce rot while big supermarts stock Dutch berries. Not because of quality, but because of perception.

Now, some people are fighting back.

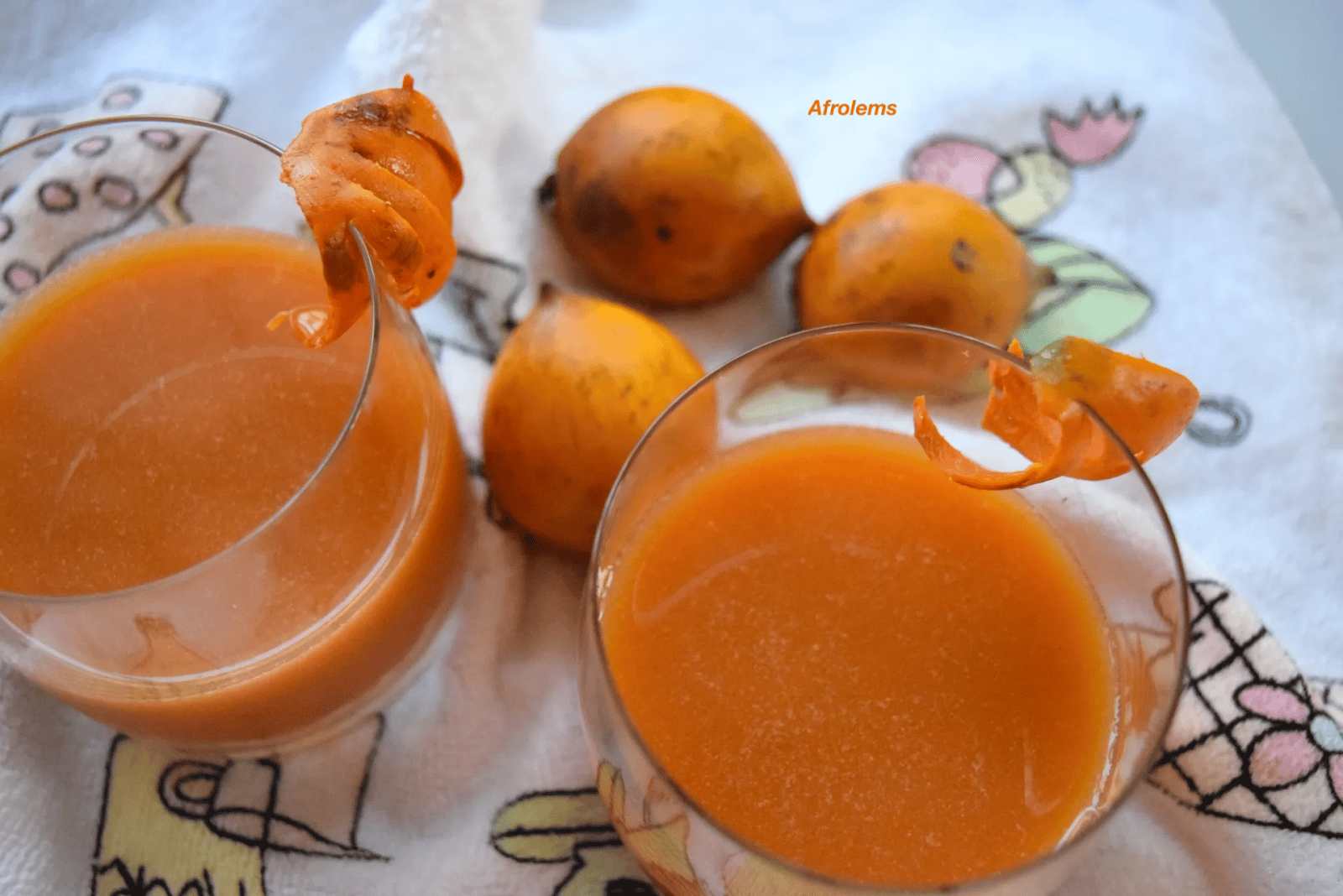

Agbulomo cocktails. Image credit: Afrolems

They're putting garden eggs on five-star menus. Charging ₦8,000 ($5.5) for agbalumo cocktails. Making heritage foods aspirational again.

This isn't about imported versus local.

It's about a food system that assigns value based on price, not nutrition.

We're creating hierarchies where none should exist.

Teaching children that some fruits are "better" based on cost. Building a society where eating healthy means eating expensive.

Food security suffers.

If your diet depends on premium fruits, then we’re vulnerable. Because exchange rates affect the prices of imported apples. Climate shifts can wreck Jos’ strawberries.

But agbalumo? Magarya? They endure.

Local farmers growing traditional crops see no future. Why grow what the market undervalues?

Some entrepreneurs see opportunity.

They're repositioning local fruits as premium.

Soursop smoothies.

Agbalumo liqueur in fancy bottles.

Cashew fruit wine for export.

The irony is perfect: to make local fruits valuable, we're making them expensive.

Some chefs charge ₦12,000 ($8.3) for garden egg appetizers. The same garden eggs that cost ₦200 ($.13) at the market.

But now they're "heritage cuisine”, they're worth something.

Maybe that's what it takes.

Maybe we need to see foreigners pay a premium for baobab before we value it.

Cashew wine and Agbalumo Liquer: Image credit: Roads and Kingdoms and Dala Lagos (respectively)

Maybe agbalumo needs to be made into an expensive drink we see influencers try on TikTok.

External validation might be the only validation we recognize.

Policy makers talk about supporting local agriculture. Investment in cold chains. Better market access.

But the infrastructure follows the psychology.

And the psychology is stubborn.

The class system in your fruit bowl reflects the class system in society. Both are getting more rigid, not less.

Next time you're at the supermarket, watch what people buy. Notice what's in your own basket. The patterns are clear.

What fruit screams "rich" in your city?

Cheers,