Hi, Hannatu here,

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) is over, and now 1.3 million jobs are on the line.

A couple weeks ago, I reported in the roundup that the 25-year trade pact between the U.S. and 30 African countries had quietly expired on September 30, 2025.

For decades, AGOA gave African goods duty-free access to the U.S. market.

Now, factories are announcing layoffs, and farmers are losing buyers overnight.

It’s the latest chapter in a recurring story, one where Africa’s economic fortunes rise and fall on policies written in Washington and Brussels, not Nairobi or Lagos.

Like this trade deal that built industries

In 2000, US president Bill Clinton signed the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) into law.

The deal was simple: give over 30 sub-Saharan African countries duty-free access to the U.S. for more than 6,000 products.

Some products covered under AGOA

For 25 years, it worked.

Kenya built a $470 million textile industry around it, employing 66,000 people.

South Africa exported juice.

Madagascar shipped vanilla and textiles.

Lesotho's entire garment sector depended on it.

The numbers tell you how big it was.

In a single year, the US imports nearly $10 billion worth of African goods under AGOA.

In 2024, South Africa alone sent out about $523 million worth of agricultural exports to the United States.

Kenya sent $600 million in textile.

These weren't just statistics. They were paychecks for families across the continent.

Kenya’s textile export to the US since 2017. Source: Kohan Textile Journal

But now, the duty-free window is shut.

Kenyan garments face 28% tariffs.

Madagascar’s textiles: 47%.

South African fruits and nuts: 40%.

Some analysts say that up to 35,000 jobs in South Africa could be at risk due to reduced agric exports.

For 25 years, AGOA helped power industries.

Now, just weeks after its expiry, the ripple effects are starting to show.

In Kenya, BBC reporters found the slowdown already underway, even before AGOA officially ended.

At Shona EPZ, a factory that normally produces half a million garments a month, output has dropped to one-third.

Shona EPZ factory. Photo credit: Hassan Lalli/BBC

And buyers are refusing long-term orders until they know what new tariffs they’ll face.

Lesotho faces even worse.

Textiles account for 56% of the country's export, and is the country’s second-largest employer.

Now factories employing tens of thousands face tariffs that could wipe out their competitive advantage.

In South Africa, citrus farmers who supply American supermarkets during winter face a similar problem.

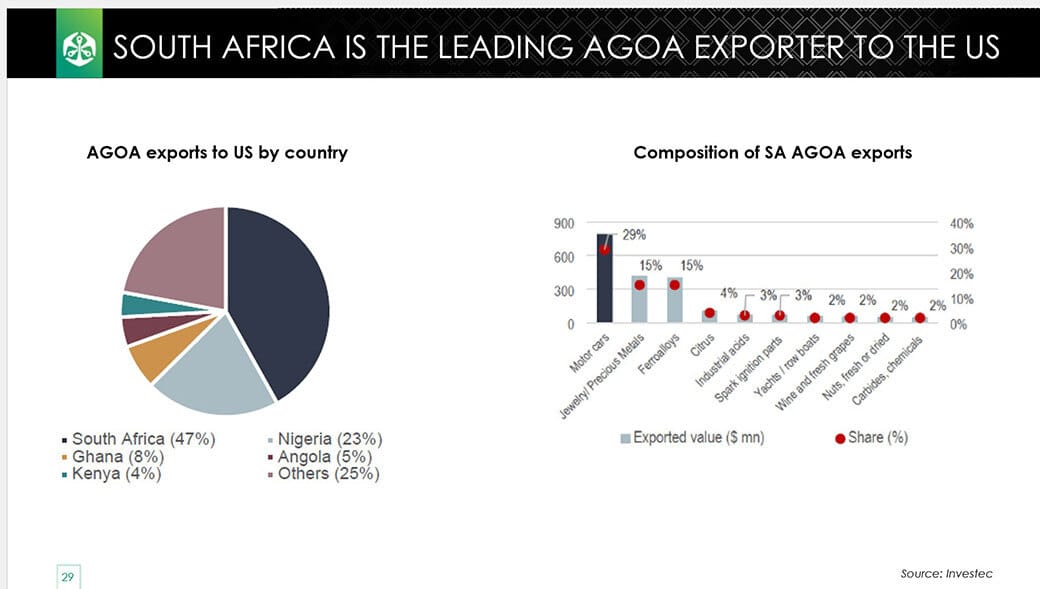

AGOA exports to the United States by country. Photo Credit: Citywire

Their exports are now 40% more expensive, pricing them out against European suppliers who pay just 17% tariffs.

The story doesn’t end at factory floors or farms, it’s part of a bigger pattern playing out across Africa’s development and trade systems.

The patterns we can’t ignore

Earlier this year, I was working in development when the aid funding cuts hit Africa's health sector.

Development programs lost budgets overnight. Countries that planned health systems around predictable US funding scrambled to fill gaps.

Now, agriculture and trade are feeling the same pressure.

The EU’s new deforestation laws, for example, are reshaping global cocoa and coffee supply chains.

And small African farmers are scrambling to meet costly certification standards to keep access to European markets.

Each new regulation or deal expiry reveals the same challenge: Africa’s growth story still depends too heavily on systems built elsewhere.

The next chapter will need to look different, one where local resilience and regional trade take the lead.

Rewriting the playbook

Some countries aren’t waiting for things to fall apart.

In the past week alone, Namibia, Tunisia, and Côte d’Ivoire all launched new national farming plans designed to build food systems that rely less on foreign markets or aid.

Kenya is pushing for bilateral trade deals while simultaneously exploring the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Last week, President William Ruto told the UN General Assembly he wants a five-year AGOA extension, but he's not counting on it.

AfCFTA now links 54 countries and 1.5 billion people, offering a framework to strengthen intra-African trade.

Unlike commodity exports, trade within Africa tends to create higher-value goods and manufacturing jobs.

The opportunity is huge, if countries actually implement it.

Meanwhile, Africa’s global trade map is shifting fast.

China has dropped tariffs on exports from 33 African countries.

Africa-China trade hit $295 billion in 2024, compared to AGOA’s $8 billion.

India, Turkey, and the EU are all expanding their footprints.

This shift helps, but it also raises a big question:

Are we really becoming independent, or just choosing new partners to depend on?

AGOA’s end shows something deeper: many African industries still aren’t strong enough to stand on their own.

Most Kenyan factories still import their machines from Asia.

Power is expensive. Roads and ports slow things down.

When trade perks like duty-free access disappear, these cracks start to show.

But this moment could also be a wake-up call.

Take Rwanda for example. After 1994, it rebuilt its dairy industry from the ground up, investing in cooling centers, better cow breeds, and local protection for farmers.

Now, it’s almost self-sufficient in milk.

It’s proof that with the right mix of policy, investment, and patience, local industries can grow strong enough to weather any trade storm.

The road after AGOA

Some insiders say Trump might approve a one-year AGOA extension.

But for now, nothing’s confirmed, and millions of African workers are waiting.

Even if that extension happens, it’s just a short pause.

One year isn’t enough for investors to plan factories or create stable jobs. AGOA worked because it gave countries 25 years of predictability.

The real goal now is bigger: building industries that can survive without special access.

That means:

Investing in energy so factories aren’t running on costly diesel.

Building local supply chains so we aren’t importing every machine.

Actually implementing AfCFTA so African countries trade more with each other.

For many workers, though, this all feels far away. They’re worried about next month’s paycheck, not trade policy five years from now.

Has your country felt the impact of AGOA’s end yet?

We’d love to hear what you’re seeing on the ground. 👉🏾Tell us here.

Cheers,

How are you enjoying Ag Safari so far?

Join Ag Safari

Ag Safari is the go-to newsletter for anyone curious about agricultural innovation and potential across Africa. Every week, we deliver tactical insights, news, and founder-led advice straight to your inbox.